From now on, you can regularly find our Instagram posts directly here on our website. Whether it’s behind-the-scenes footage, inspirations, or highlights, we’ll share with you everything that makes up the world of Ladislas KIJNO.

Stay connected and enjoy our latest news at a glance. And for even more exclusives, don’t hesitate to follow us on @comiteladislaskijno!

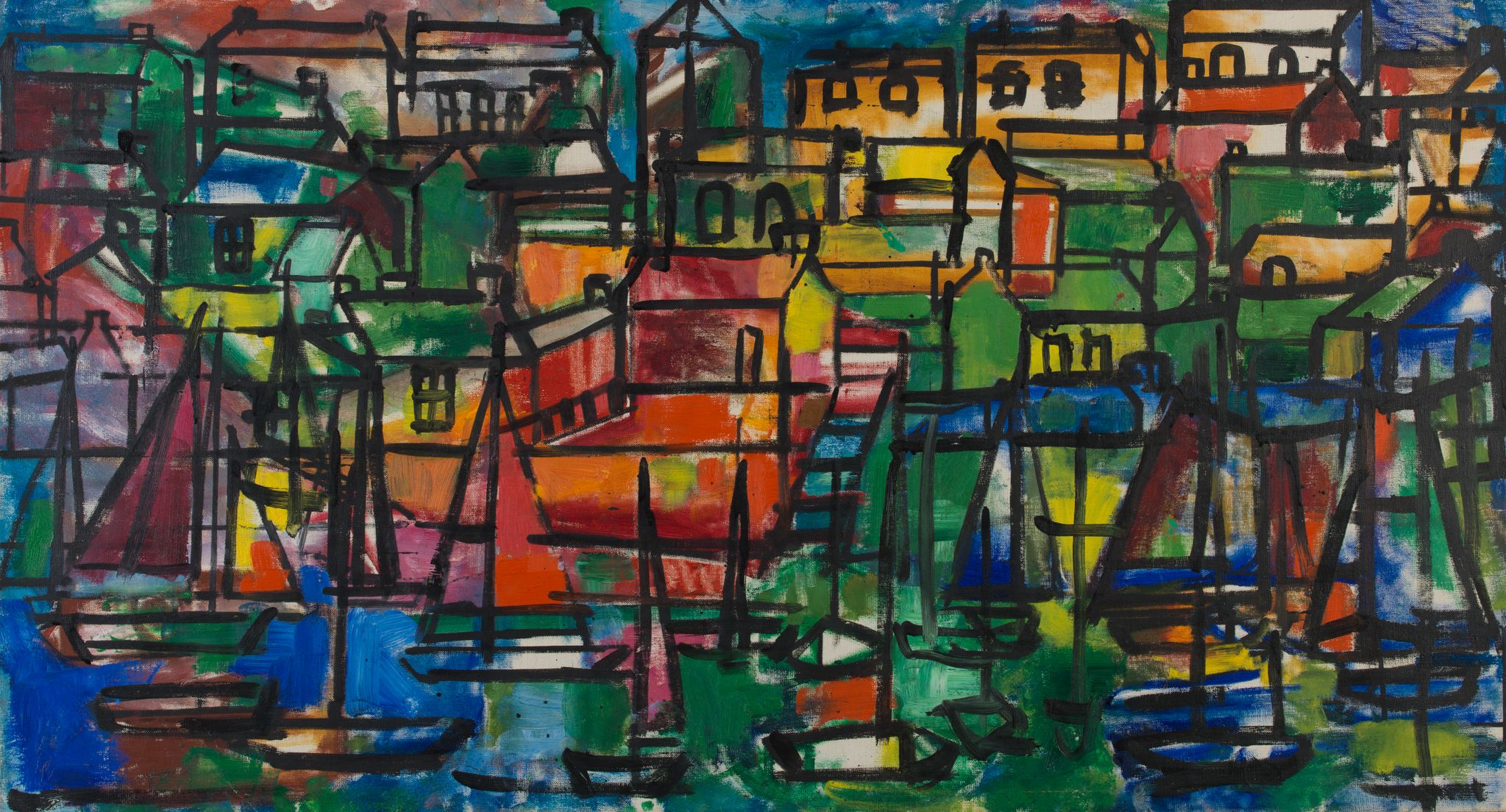

On January 14th, we were very happy to exhibit Ladislas Kijno in Monaco, an opportunity for collectors to discover or rediscover the work of Ladislas Kijno

View this post on Instagram

We had the pleasure of welcoming the team from TV Monaco’s morning show to the Ladislas Kijno committee.

We thank Mr. Anthony Alberti and the production team for this wonderful spotlight

View this post on Instagram

- Gilles Plazy

- Dominique De Villepin

- Salah StéTié

- Raoul-Jean Moulin

- Jean Grenier

- Bernard Dorival

- André Darle

- Bernard Vasseur

- Charles Dobzynski

- FrançOis Xavier

Gilles Plazy

Writer and photographer

Lille, January 2006

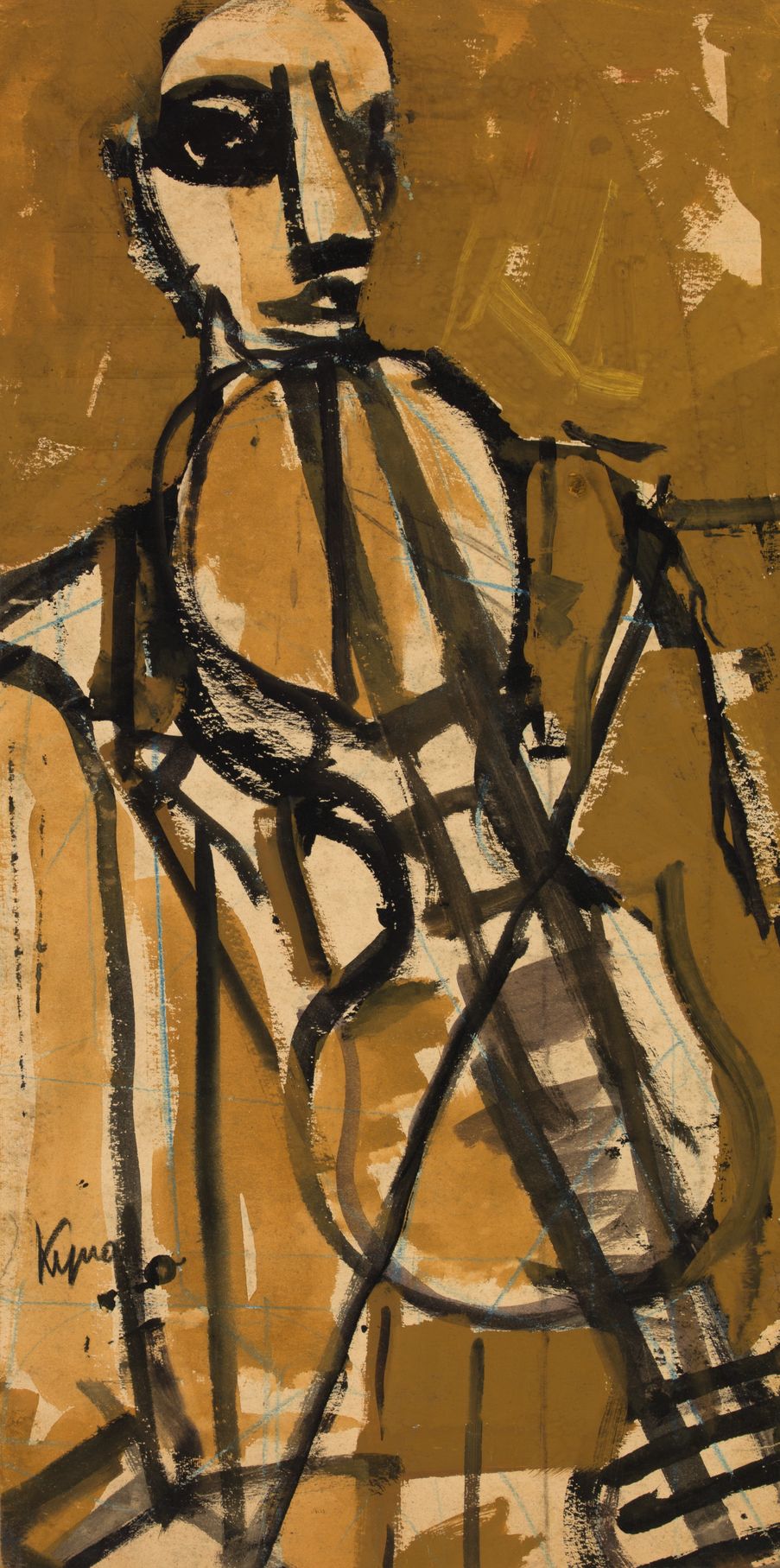

Not very understated, powerful, self-assured, original, the expression of a triumphant painter who asserts himself with panache in the art of his time, Kijno’s painting imposes its evidence, but the essential is not there. It’s behind the skin of the painting, in the ardent questioning that stretches such a profusion, turning it (for those who see beyond the pleasure of the eye) into vertigo, because Kijno is for himself the field of an experience that is not ridiculous to call metaphysical, of which painting is the seeing medium, but which is also expressed in an abundance of texts mostly not yet disclosed. One day, we will delve into his numerous notebooks and we will undoubtedly better understand from which black hole the intense energy that his work exults was born. That it presents itself as a series of accomplished forms does not prevent us from taking it as so many signs that mark an exceptional life, demanding, tormented, led gropingly in the darkness that is our common place, in search of an absolute that it knows is only hope, a mirage, but which is for it the only reason to remain tense above the void.

Painting for Kijno is an adventure of existence, not just passion (for a painter, the least of things), a total commitment of his personality in a quest for who knows what, the meaning of life, the “enigma of” being, truth, accord with the world, understanding with oneself, fullness, safari… Everything that makes a man obtuse goes forward, lucid and blind at the same time, in anxiety and enjoyment, anguish and intoxication. But with an energy that is his particular lot, oversizing the adventure: excess is natural to him, breath is his reason, his gesture throws his thought forward. Kijno’s painting, although often handling image, is much more than what it shows to the superficial gaze, because, for any painter who matters, the painting (the canvas, the paper) is never more than the skin of some unknown being, undoubtedly a double of the painter, on which are inscribed signs that no key allows us to decipher, beyond some meanings too simple to be exhaustive.

Kijno, we think he paints, that he celebrates signs and colors; in fact, he bores. He digs the path of his existence, of his truth which are ours if every man is an example of his fellows. The philosopher goes with the interweaving of concepts, the poet with the ignition of language, the mystic with a dizzying return to oneself, the painter, he needs to see, not paint what he sees, but to see.

Kijno collects himself with reality to draw signs that will allow him to see more clearly. Thus the gaze, in constant mutation, oscillates from reality to painting – and the painter does not immobilize himself in the assurance of some thought either. Painting is alive only insofar as it is a new and singular experience of a quidam engaged in a radical questioning of the world, of man and of man’s relationships to the world, that is to say to life and death. But painting is not language. It does not think with words and ideas. It is a practice producing objects. It thinks with gestures, materials, signs, colors. Kijno’s painting may cultivate signs, these do not operate in the order of pre-established meaning, they emerge as emblems, steles, coats of arms or beacons.

Naturally, one sees assurance there. Except that so many affirmed signs are also often denied by a contradictory action of the painter. Even before painting, instead of meditating before a blank canvas or page, respectful of so much candor to invest, he crumples kraft paper, into a ball as if to throw away, similarly kneads the fabric, coated or not and not yet on the frame. A violence that brings the support to life, before the paint comes, already a drawing, at least an animation of the matter, a network of lines, formation of relief. Crumpling has become his style, thus violating the smooth propriety of Fine Arts. The crumpled-collages, often already spattered with splashes, he sometimes also tears them apart to force them to show their flesh. And what if it were an operation of metaphorical magic to force painting to become flesh? The agnostic who was once a seminarian and who keeps the sense of myths at the highest level would probably have nothing to say about such an allusion. A question, yes, of skin. Of what can be read on the skin and what is hidden on the skin. Under the paint smolders a fiery blood, pulsates a man’s flesh, a man’s conscience.

Head down in painting, Kijno cultivated speed, produced prolifically, prolific and protean. This painter himself is many. Which does not facilitate categorization. In bulk, painter of abstract expression, figurative in the Picassian lineage, history painter, primitivist enamored with Africa and Oceania, iconographer of Christian or Buddhist inspiration (tearing and serenity), aggressive tachist, obsessed with sculpture, valiant portraitist, graffiti artist… And always between apologetics and revolt. Also: sometimes a howler, sometimes meditative.

At the bottom of the mine that painter Kijno digs and from which he brings back explosive nuggets, there is a secret man, silent, light, meditative, transparent. The painter knows this, just as he knows that he will only perfectly rejoin this other self in that final hour which would be less a dissolution than the seal of an accomplished life. This is the reverse of the public Kijno, abundant, enthusiastic, eloquent, good at the table, seductive, good actor, fascinating memoirist, warm friend, impetuous host, agitated traveler, voracious reader, compulsive scribbler… It’s the white face of the man struck by metaphysical stupor, the one that rarely allows itself to be seen behind the features of the face, as observed in ordinary times or as photography can capture it. This man has put himself to the test of painting, using it to shed the scales of fear and prejudice. He has put all his trial into painting, seeking to unbind it in the unpredictable rise of signs. Younger, he was tempted by other paths, religious illusion or the spinning of concepts. Painting prevailed, became his destiny, the place of risk and the only recourse. It has never given answers except in the moment, ephemeral fullness, temporary solution. Otherwise, it would have stopped. Painting has never saved a man. Many have even lost themselves in it. To painters, it never allows lasting a little, by living intensely. To others, it matters that it is there, presence, a wall on which a trace of man is read, a parchment on which an inexhaustible text is deciphered.

Source: exhibition catalog Kijno at the State Russian Museum

Photo credit portrait:

Transcript of Dominique De Villepin’s Speech on the Occasion of the Opening of the Exhibition ‘KIJNO’s Great Utopia’ on March 17, 2017

Dear Malou,

Mr. Mayor, dear Emmanuel Lamy,

Dear Arnaud Péricard,

And dear Renaud Faroux, Exhibition Curator

First, I must say that this is an immense emotion for me.

The shock upon entering this marvelous place, this place inhabited by Lad is quite extraordinary, even more so when one encounters this ‘Kijnosphere’ which so well reflects the world that was his, the world from which he derived, which is a world of art.

A world of art where everything is an encounter and I must salute the brilliant intuition behind this exhibition, this title ‘The Great Utopia’ because I believe it does justice, it renders justice to a man who very early on had the intuition of an extraordinary ambition.

‘The Great Utopia’ yes that’s indeed what it’s about and which shows well at what level the gaze, the work, the humanity, the generosity of Lad Kijno rises.

“The great utopia”, imagine that the dialogue between artists can take place across centuries where Uccello, Mantegna, can converse with Robert Combas whom I salute as well as Geneviève.

“The great utopia” of art where poetry meets and neighbors painting.

“The great utopia” of a world where philosophy dialogues with painting.

“The great utopia” where man finds himself at the center.

And, Renaud Faroux was pointing out to me earlier on each painting how Lad doesn’t confine himself to any school, to any chapel, no matter how great it may be.

Of course, the lyrical station more often the label that was attached to him, but there is in each of his paintings a center, an image of something that exceeds and overflows, a sphere, a heart, a beating heart.

And this strength, this originality clearly shows his constant concern to go further and this ambition touches me, I believe I can say, touches us all particularly today.

We are not in just any world, we are in a world more than ever wounded, more than ever painfully scalded by tragedies, tragedies that find an echo here, the echo of what was and what continues to be the work of Lad Kijno, those who suffer, refugees, the left behind, all have a place in this work, all these crumpled faces, all these dented images account for a world where art, humanity are permanently the main actor.

“Great utopia” again when it comes to giving hope to man and what a lesson for our time, hope when it comes to giving direction to our ambition, to our societies, when it’s about never separating man from his life and we find everywhere this story that constantly surpasses the work he does.

The Vietnam War, Angela Davis, the Algerian War before and so many images against which he fought, the Iraq War that had so deeply wounded him, permanently this refusal of this fatality, permanently the concern to push forward this heart of man that can change everything.

Because indeed, “The great utopia” of still believing no matter what the trials, whatever the difficulties, that’s what makes Lad continue to speak to us, this hope he brings us, these words that continue to “be so alive in each of his paintings, I believe that the look that many will have on these works shows how unique the ambition is, the ambition is immense, the ambition for something else, for a better world is constantly present, and I must say a big bravo to the Town Hall of Saint-Germain for having taken an initiative of this ambition, a big bravo to the Exhibition Commissioner because he gives us the opportunity to see again the” work of Lad, and Lad this great artist, this friend is present in each of his works, he is present among us here and there was in Lad’s heart and how many times with Marie-Laure we experienced it in Sunday lunches constantly this concern to give. And this is what makes him a very singular artist, here’s an artist who didn’t count, here’s an artist who didn’t worry about the end of the month, here’s an artist who shared his work with the sole concern of making art live, not the artist’s rating and we can see that the artist’s rating will finally be there at the end of the road anyway because this work is stronger than the market, it is stronger than small accommodations and small interests, there is a man here, a man who has been carrying since The Lascaux cave always the same ambition to change the world, so for this great utopia, thank you to the heart of the work let’s not forget, there is a figure that is present everywhere it’s that of Malou, who is almost in her fighter plane tonight and who is the beautiful figure who accompanies him, who accompanied him and who gives us so much friendship and so much joy.

Thank you Malou and thank you all for being here tonight.

Salah Stétié

Poet, writer

Former Ambassador

In “Blind Window” Rougerie Editions 1998

For anyone, a crumpled paper is disposable; for Kijno, it’s a living paper. Suddenly, this paper, mistreated by the painter’s hand, becomes covered with veins and venules, arteries and arterioles, and, quite miraculously, metamorphoses into animal or vegetable tissue, returning to its original nature, to “the primary element it should never have ceased to” be. Once again skin or parchment, cross-section of a tree trunk or constellation of sawdust, it has – as one says of someone who has fainted – “come back to itself”: returned to its doubts, its hesitations, its crossroads, its wrinkles, to that undoubtedly highly ontological stage where matter is no longer matter, where mind is not yet mind. The most immediate enigma of a paper crumpled by Kijno’s fingers is that it instinctively poses the problem of origin.

There is also this crumpled paper metaphorically returning to its immemorial matrix – be it animal or vegetable – which will learn, through some inherent science, to burden itself with a density denser than life, which everyone knows is ephemeral and fragile. And what is more ephemeral and fragile than a sheet of paper, even if it’s the kind used for packaging? There is nothing in the world incapable of crushing, puncturing, smashing, rolling, tearing, “crumbling, or burning it. But Kijno, the” astonishing Kijno having come, and his fingers also having passed by, here is the paper, skillfully damaged, dreaming of being mineral, becoming not just tissue but texture – a swelling of light lava signifying that the primitive substance of the universe, without being truly alive, is not inert either, and that it is traversed. I believe I see in “the least elaborate state of a Kijno paper, long before the intervention of the most personal traces and signs, which are all opening keys, I believe I see, I say, his intuition of cosmic material. But is the material the material, is matter matter, and are they not already, by the simple fact of” being called into existence, spiritual flashes? In another context, yet the same, Saint Teresa of Avila asks the question: “”I don’t know,” she says strangely, “if money is a material or spiritual thing””. And Kijno’s crumpled paper, his basic material, his starting element? We don’t know either.

Source: “”fenêtre d’aveugle”” Editions Rougerie 1998 – catalog of the Kijno retrospective at the State Russian Museum of Saint Petersburg, 2006, Palace Editions

Raoul-Jean Moulin

Essayist and art critic

Honorary General Secretary of the International Association of Art Critics

Kijno never met Neruda – he only approached him during the honor guard for Elsa Triolet’s mortal remains – but their encounter did take place since his painting attests to it. “Through the votive, fraternal celebration of the liberation struggles of peoples, the most beautiful, the greatest, the poorest, I am perhaps a non-Western painter, I the emigrant, the exiled, the heterodox always in dissidence, a painter of mixing, of the syncretism of primary forms,” he affirms.

Folds against folds, rhythms against rhythms, crumpling, uncrumpling, in some way relay the impulse of the gesture and its trajectory, substituting for the inscription of its sign on the canvas spread on the floor, to its deployment all over. Disturbing the brush strokes and spray can pulverizations, the wrinkling of the fabric, at the end of its preliminary general retraction, simultaneously and contradictorily produces the contraction and expansion of the writing, a potential extension of its chromatic field. It is necessary to paint, imprint an increasingly vast support, fold, refold and unfold, crease and uncrease this textile weave taken by the agitated impregnation of color, manipulate it by exploiting the unpredictable configuration of the creases, work more physically, more directly than before on what it hides or reveals, what it breaks or brings together, what it grafts, what it generates, the entire and new texture that emerges from the abruptness of the hand, from the impetuous passion of painting, and which constitutes Now the materiality of the image or the trace of its sign. Crumpling is blind; it knows the place of its intervention but ignores what it operates on: it doesn’t know what it crumples. It relies on chance, intuition, possible failure, a random finality. It reveals the whites of the canvas, the unpainted, fortuitous reserves, parsimonious, to which are added, as if by breaking in or detaching, the creases left in the hollows of the reliefs, in the depth of pressed, compressed folds, the accident of hidden color suddenly revealed, partially discovering between the cracks a buried polytonality, a previous fire illuminating the truth of painting.

Source: Monograph Kijno, Raoul-Jean Moulin, Editions Cercle d’art, Paris 1994

Jean Grenier

Philosopher, Teacher of Albert Camus

“The Choice of a Critic”, L’œil n°46, October 1958, Paris

“Eventually the fig trees and pebbles, what is outlined against the sky, what is outlined on the seabed, present analogies as one discovers in families of numbers and figures ‘studied by mathematicians’. This passionate research has led an avid mind like Kijno’s to descend to” what Cézanne called “the foundations of the world”.

Source: catalog of the Kijno retrospective at the State Russian Museum of Saint Petersburg, 2006, Palace Editions

Bernard Dorival

Former Chief Curator of the National Museum of Modern Art

Professor at the École du Louvre and the University of Paris Sorbonne

Paris, January 1st , 2000

My dear Lad,

IT HAS BEEN EXACTLY HALF A CENTURY SINCE I MADE YOUR ACQUAINTANCE. You were very young then and I “wasn’t yet old. I” had come from my holiday residence to the Assy plateau to meet our friend MAROIS. It was he who had the idea to introduce me to you.

You lived among people of quality, the DEGEORGES, the TOBES, the DORMEUILs, not to mention the admirable Canon DEVEMY who provided you with your first opportunity to show your measure as a painter. It was this Last Supper in the crypt of Notre-Dame de toute-Grâce where, with the naivety and unconsciousness of your twenty years, you overturned traditional iconography in favor of a new and poignant iconography. Later, I had the opportunity to meet your mother in the coal basin of Pas-de-Calais, whose faith in you I admired – a faith shared by your wife Malou, of whom it can never be said enough what help she was and is to you in your life as a man and an artist.

This artist, I have amicably followed your journey, a journey that you have lived under the sign of independence. Blind and deaf to slogans and trends, you are a free man, which is not so common in today’s art. You have made, and still make, the painting that you need to make, the one that your inner necessity pushes you to create and which makes it a long confession, a moving confession of your soul (allow me this outdated word now; I see no better one to characterize your painting).

This painting has evolved a lot, fortunately, over time, but it has remained, fortunately again, itself. What defines it, if I’m not mistaken, is first your gesture.

Authoritarian, imperious, imperial, it lays on your supports, a rather economical matter with such assurance that one could not contest the force resulting from this movement of your wrist to your hand. It’s a fact, as is your presence. And the second major component of what you create is light, your light, a light that you have found the means to multiply by your invention of your crumpled papers. Indeed, by crumpling a previously painted paper, you create edges that allow light to play and hollows that remain in half-shadow. The surface of your work is nothing but quivering, breathing, life, a bit like those mountains of the Assy Plateau where we met. Drawing, color, matter are, in this way, subjected to the form you love, simple and evident, reigning over the support, but also doubling its plasticity with a lyricism and, even better, a spirituality that make your painting, a total expression of yourself, address the totality of your viewer and make all their most intimate fibers vibrate. Your art is dialogue, and that is enough for everyone to admire and love it.

Well done, Lad, and see you soon. You know my friendship.

Source: catalog of the Kijno retrospective at the Russian State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg, 2006, Palace Editions

André Darle

Poet

In “Kijno, Tzara, Aragon, Ponge”, Cercle d’Art, Paris, 2004

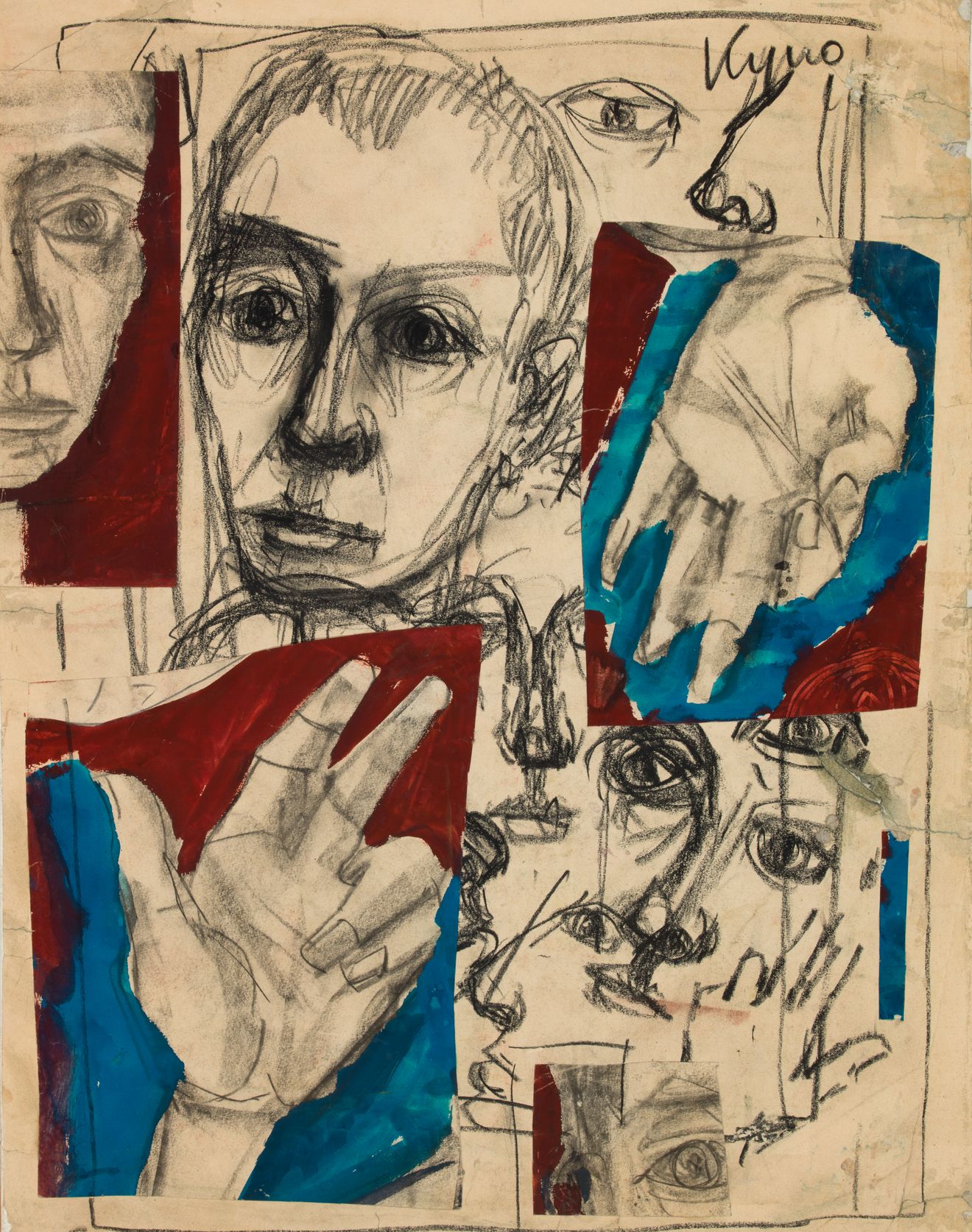

As the year 2000 approached and in the confusion of the times, after this hurricane passage, this sudden tremor over France, I hardly knew what to think when the telephone rang. Ladislas Kijno is one of those artists who knows how to awaken and dazzle. He had just drawn seven portraits of Tristan Tzara and wanted to tell the one who had talked to him one evening about a project concerning the poet. The publisher wanted to place a drawing on the cover of the book I had provisionally titled: Tristan’s Laugh. I knew that the painter, one of today’s most prestigious, had once crossed paths with Tzara in Antibes. But how could one imagine that something was beginning with the millennium, of the order of creation and memory? How could one imagine this series of “psychoanalytic” and soon crumpled portraits, seven at first, then forty, fifty a few days later, finally seventy…

Like great predecessors yesterday, Matisse or Picasso for example, Kijno passionately extends each new creation. But I am only sketching an approach here, as it is true that in great creators, areas of shadow often remain. Otherwise, how can one explain the unique accent, the happiness of expression achieved in some unknown way, the perhaps inexpressible?

Should it be specified that Tzara’s friends, his companions of surrealism (Louis Aragon, Breton, Desnos, Eluard…) appear in this prodigious graphic ensemble? A disconcerting era reappears here with the unparalleled brilliance of the imaginary.

Bernard Vasseur

Philosopher

Director of the Elsa Triolet and Louis Aragon House

in Saint Arnoult-en-Yvelines, France

(…) Let’s transpose and observe: Kijno composed his Tzara variations like a Dada poem: ink, scissors, glue, crumpling… An automatic writing creating its magnetic fields. An exquisite corpse. “Surrealism is within reach of all unconscious minds” proudly proclaimed a 1925 tract. “Poetry must be made by all (and not only for all)” wrote Isidore Ducasse. You too, can crumple-uncrumple. Another way of saying that poetry is a vital function and that every individual can burn themselves in its fire, as they breathe. But it requires a rough twisting of being: going back to the source of emotions, below received opinions and beyond all convention.

The poet and the painter are not exceptional men, apart, inspired, visited… Literature is not, even slightly, an art of embellishing others’ leisure. Poetry, painting are not academic “genres”, purely aesthetic activities for an informed and well-bred public, one-night shows in a gallery or theater. They are ways of life, ways of being. “One only needs to take the trouble to practice poetry,” says André Breton in the Manifesto of Surrealism. It is ready to spring forth at any moment from the world that is ours if one knows how to see and hear it, and finds its place indifferently in literature, painting, dreams, wordplay, a simple street incident… It is a violent absence to a world of violence and contradictions. It carries one to the summit of oneself. It introduces by breaking and entering, if only for a few moments, to the “surreal”. It opens us to the invisible. “Before what we see, we must think of what we don’t see, and which is there, manifested,” writes Bernard Noël.

In dialogue with Tzara, Kijno does not illustrate Tzara. He does not put the texts of the poet Tzara into images. He vibrates to the deep rhythm of the same blood. Look at Tzara’s dark gaze, it takes you elsewhere, it forces you to travel. Kijno likes to quote this formula from Leonardo da Vinci: “La poesia è una pittura cieca e la pittura è una poesia muta”. (…)

In “Kijno-Tzara-Aragon-Ponge”, Cercle d’Art editions, Paris 2004

Photo Claude Gaspari

Charles Dobzynski

Poet, writer, editor-in-chief of Europe Review

Is the painter solely the one who gives to see, according to Paul Eluard?

No, it’s the one that transforms the view, sometimes completely. Ladislas Kijno belongs to this Promethean family of fire thieves. He carries our gaze far beyond appearances. Where it burns. Where it sings. His painting encourages us to see differently, to see more deeply. So much so that seeing becomes a writing even more than an appropriation. That fiery something in it relates it to poetry. What it burns is its resurrection; it’s the phoenix of color and form. The poet’s words not only align with this world in constant gestation, this world that reinvents the gaze, they draw their energy from it. Rarely have painting and poetry found such a point of conjunction. The sight nourishes the lava of language and fertilizes it. Accompanying Kijno in his work, as has happened to me, is a joy. The joy of discovery. A renewed conquest. Dreaming and being reborn at the same time.

Source: catalog of the Kijno retrospective at the Russian State Russian Museum of Saint Petersburg, 2006, Palace Editions

François Xavier, La Romania, 2010

“Always indignant, always protesting, furious, waging his passionate and endless battle to impose painting as a balm on the hearts of men, Kijno dresses colors, blows hot and cold, meditates with his pencil while on the phone and asserts his solutions on crumpled papers.

He works tirelessly, burns his seven lives in the love of art clad only in an armor of light. He tyrannizes fools, charms and fascinates, imposes his creative and contradictory force in the radiance of his suffering that becomes painting. Kijno is the painter of presence outside the norms of abstraction or figuration because he is above all the one who loves.”

—-

Tribute to Ladislas Kijno

Calligraphy of spring your bodice opens gently

On promises of summer and other torments.

Here the spread star is dying

At the nascent day in the escapade of its madness

Recovering the idea of another death

In the sight of the sun which is night

: two magnificent breasts sprung from nowhere

To bury one’s face in

And see nothing more.

Source: Extract from Kijno e(s)t l’art d’aimer, éditions du Littéraire, before Bernard Noël’s foreword, 2013